•

Written By

Written By

•

•

•

Loading article...

Written By

Written By

Written By

Omar-Rashon Borja

Senior Writer, Editor, Historian

Written By

Omar-Rashon Borja

Senior Writer, Editor, Historian

The 1966 Game of the Century between Michigan State and Notre Dame, one of many in the College Football lexicon, lives on due to its infamous 10-10 result and Ara Parseghian’s late-game cowardice. Despite its indeterminate result, its impact reverberates to this day. Perhaps it was the day that college football became a truly national pastime. At the time, NCAA rules allowed schools to appear on television three times in a two-year regular season period with only one national TV appearance allowed. Complaints throughout the country rang and ABC had to bend the rules to most of the country (48 out of 50 states) to see the game live, with the rest watching on tape-delay.

More importantly, the 1966 Game of the Century was a turning point in college football’s integration story. Michigan State and Notre Dame’s clash showed off the Spartans’ diverse lineup to the country. It is a game Jesse James considers paramount to the Civil Rights Movement. Nearly 60 years later, Michigan State welcomes an HBCU for the first time in a game that pays homage to both Black College Football’s rich history and Michigan State’s trailblazing role in college athletics.

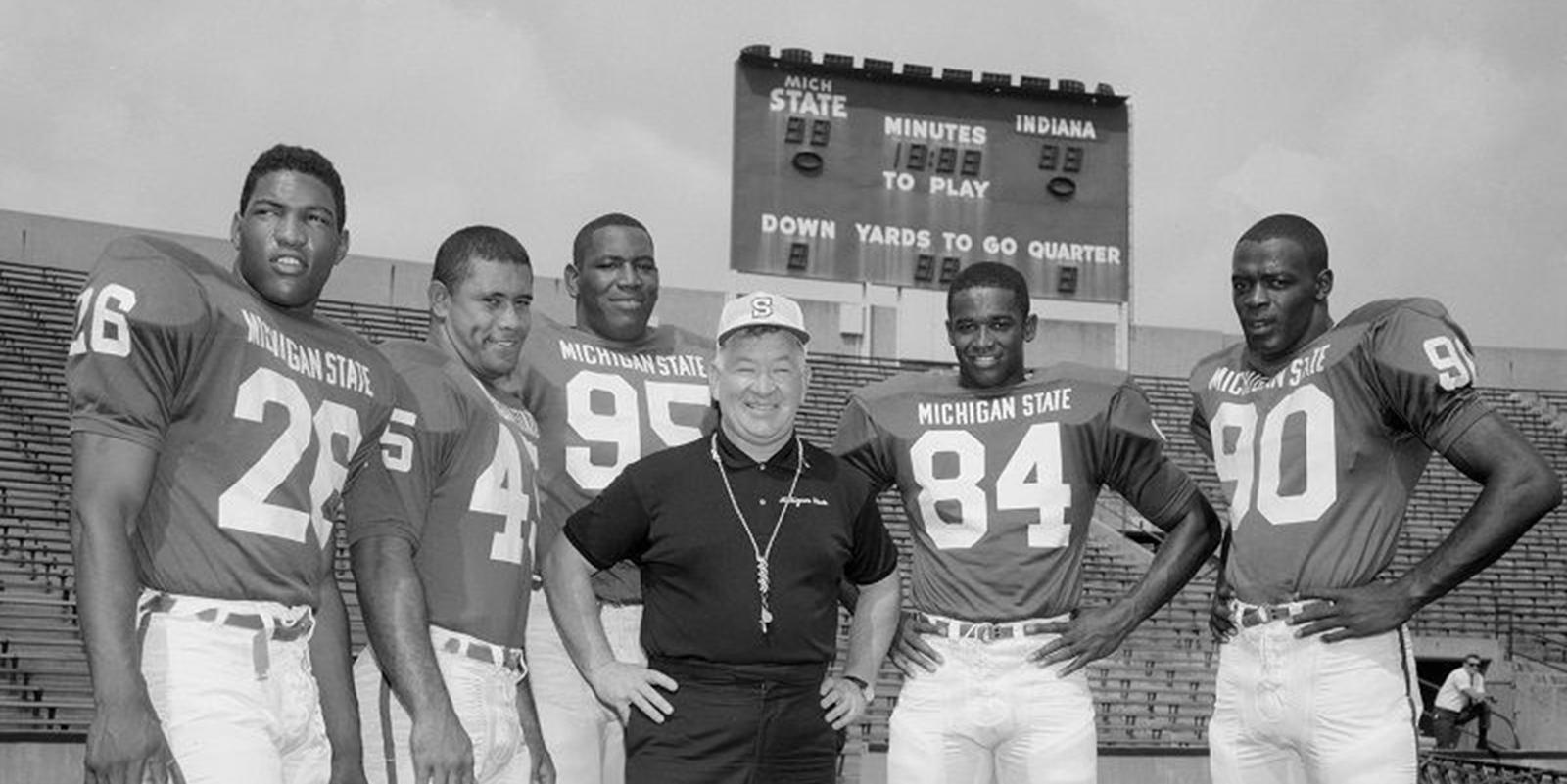

While not the first time Black players had shared the field with White players, the 1966 Game of the Century reminded rest of the country that times were changing. Bubba Smith, Gene Washington, and George Webster were Black stars who headlined a Michigan State defense still regarded as one of the most fearsome defenses ever. Jimmy Raye, a rare Black quarterback of the era, led the Spartans' offense. Bob Apisa’s exploits in the running game made him the first Samoan All-American. A host of other Black players, lauded less by the media, were still integral to the success of that 1966 Michigan State squad. Perhaps even more fittingly, this particular Game of Century featured Notre Dame, college football’s most famed and polarizing program, as the Spartans’ opponents.

Since the most contentious moments of the Civil Rights Movement occurred in the South, most sports historians leave out the Game of the Century when recounting crucial moments in college athletics’ integration. Historians focus on other moments like the Game of Change when Mississippi State defied Governor Ross R. Barnett’s orders against playing an integrated Loyola-Chicago squad in the 1963 NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament, or USC running back Sam Cunningham convincing Bear Bryant of the necessity of integration in 1970 by running for over 100 yards and two touchdowns against the Crimson Tide.***

Michigan State has always been a trailblazer. Thirteen years before the 1966 Game of the Century, the Spartans gave the Big Ten its first Black quarterback when the aptly named Willie Thrower helped lead Michigan State to the 1952 National Championship. Thrower lives in relative anonymity to many college football fans, but he was a pioneer. In 1953, he became the first Black Quarterback to appear in an NFL game since the league’s “gentleman’s agreement” in 1933 to unofficially bar Black players.

This integral role in opening college athletics to all races makes their first game against an HBCU long overdue. Needing a non-conference replacement after Louisiana backed out of its 2024 game with Michigan State, the Spartans scheduled Prairie View A&M to complete their slate. The Prairie View A&M game represents a crossover unlike any seen in the Big Ten. Although not a brand name that casual fans can easily recall such as Grambling, Southern, or Florida A&M, Prairie View has a rich history.

Before the 80-game losing streak from 1989-1998 that made the program the answer to a dubious trivia question, Prairie View produced notable pro football talent. At their peak, legendary Eddie Robinson hated playing against them. Under College Football Hall of Famer Billy Nicks, Prairie View amassed a 128-39-8 record in his two tenures as coach from 1945-1947 and 1952-1965.

Before Daron Bland broke the NFL record for most interception returns in a season this past year, a pair of Prairie View grads, Jim Kearney and Hall of Famer Ken Houston, held the record since the early 1970s. Those who grew up watching cinematic NFL Films Super Bowl highlight reels have likely seen Kansas City Chiefs legend Otis Taylor’s lanky stride to the end zone for the clinching touchdown in Super Bowl IV. He also was a Prairie View product.

Moreover, Michigan State and Prairie View A&M share more similarities than meets the eye. Both schools have made significant contributions to Black involvement in College Football. Unfortunately, College Football fans overlook both school’s contributions to the game’s integration. A natural tendency to look to the South for pivotal moments in American Civil Rights draws attention away from Michigan State’s contributions. Prairie View’s elite run as Black College Football royalty ran concurrently with the tenures of legendary coaches Eddie Robinson of Grambling and Jake Gaither of Florida A&M. Consequently, several college football experts do not consider Prairie View A&M as an HBCU blue blood.

The Prairie View A&M-Michigan State game is a reverent moment for college football. Prairie View is an institution whose existence came as a response to Jim Crow. Michigan State led the charge in making college football accessible for all races. Although they are different, their paths come together. It is difficult to tell the story of College Football without either. When the clock hits triple zeroes on September 14th, several fans will likely forget the score of this game. However, they should not forget the contributions of both schools to making college football a pastime for people of all backgrounds. This game reminds fans of the long road to racial inclusion in college football.

***I am one historian who did not lose sight of the 1966 Notre Dame-Michigan State game’s significance in sports integration. I dedicated a paragraph of my thesis to it, which you can read "THE LONG GREY ROAD TO SPORTS INTEGRATION AT WEST POINT."

Michigan State adds Prairie View A&M to 2024 football schedule Details:⬇️ fbschedules.com/michigan-state…